WOLFE von LENKIEWICZ

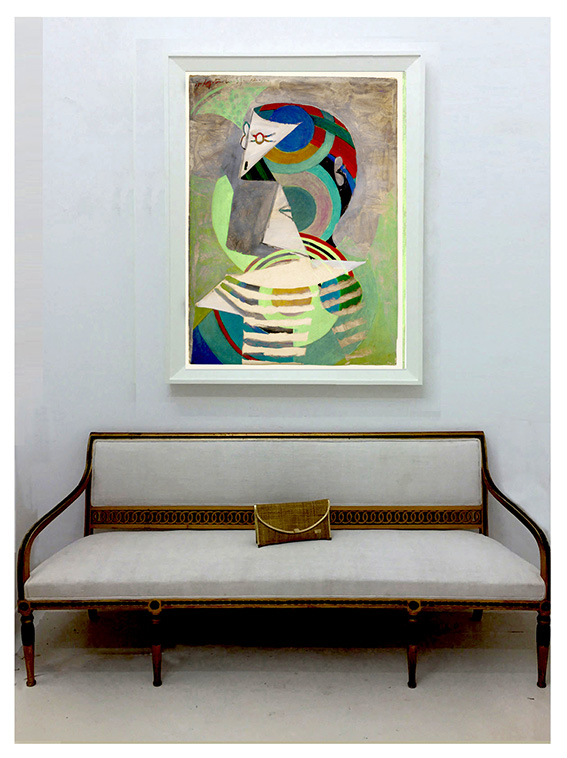

'Woman in the Red Hat'

oil on canvas (2017)

84 x 70 cm

in bespoke, gilded artisan's frame

oil on canvas (2017)

84 x 70 cm

in bespoke, gilded artisan's frame

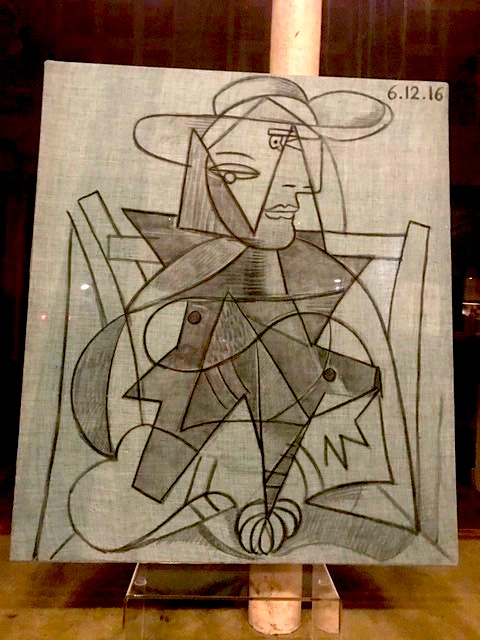

'Tete de Femme'

charcoal on bookbinder's linen (6.12. 2016)

60 x 70 cm

charcoal on bookbinder's linen (6.12. 2016)

60 x 70 cm

The Duchess of Polignac

oil on canvas (2016)

80 x 70cm

oil on canvas (2016)

80 x 70cm

Portrait of a Man

oil on canvas (2016)

140 x 110 cm

oil on canvas (2016)

140 x 110 cm

La Grande Jatte' (Sunday Morning in the Park)

oil on canvas (2016)

200 x 300cm (unframed)

oil on canvas (2016)

200 x 300cm (unframed)

Leda and the Swan (2016)

Oil on canvas

200 x 130 cm (framed)

Oil on canvas

200 x 130 cm (framed)

Fall of the Rebel Angels (2016)

Oil on canvas

120 x 160 cm (framed)

Oil on canvas

120 x 160 cm (framed)

Velazquez Dwarf (2016)

Oil on canvas

100 x 130 cm (framed)

Oil on canvas

100 x 130 cm (framed)

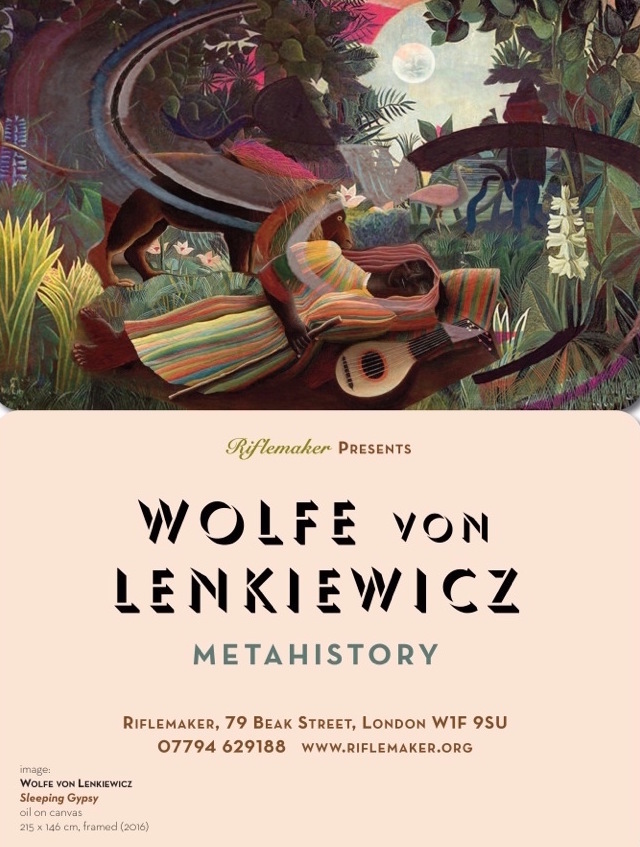

WOLFE von LENKIEWICZ

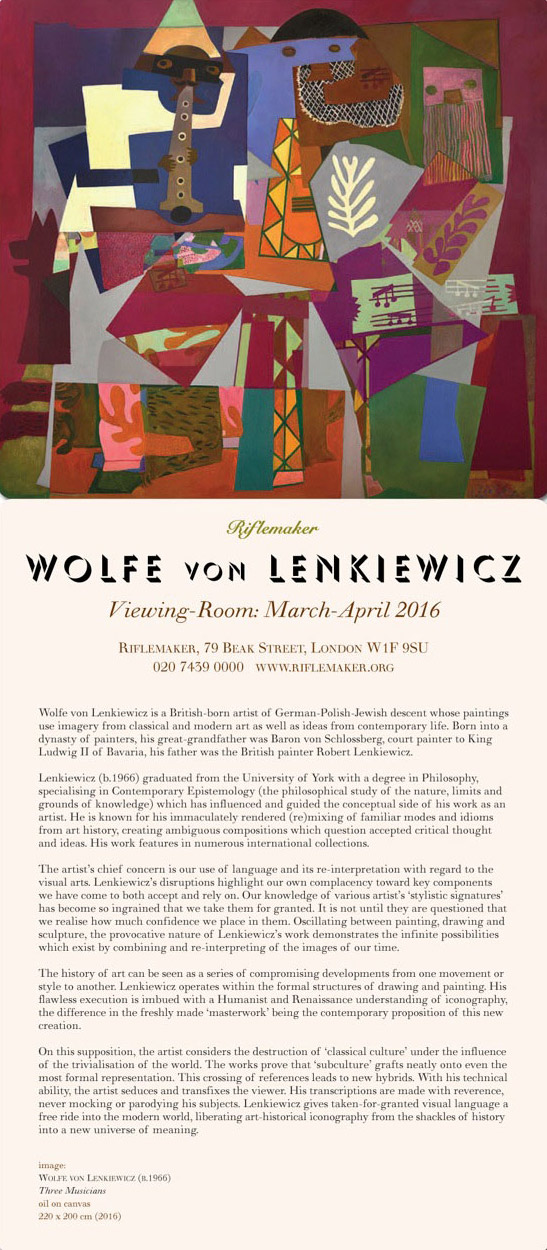

MetaHistory

Wolfe von LENKIEWICZ (b. 1966) engages with the entire history of both classical and contemporary art by referring to key works in our visual consciousness and to the history which surrounds them. LENKIEWICZ is from Polish origins, descended from a dynasty of painters, his great-grandfather was the court painter to King Ludwig II of Bavaria.

Wolfe Lenkiewicz’s paintings propose a ‘metahistory’ of art, breaking with official history to fashion a new mythology - a history about the history of art.

In Postmodernism: Or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991) Fredric Jameson posited modernism as a critique of the ‘commodity’ and postmodernism as the consumption of commodification. Under postmodernism the act of consuming itself became a commodity. LENKIEWICZ does not position himself as a singular artist who, by his unique and extraordinary creations is going to change history. Instead, operating from the position of a meta-postmodernist observer, he investigates our mythological construction art history as a fiction - much as an improvising jazz pianist may outwardly appear to be in ‘free' improvisatory mode but subjectively may be referring to (and listening to) the exquisite harmonic sense of the music of JS Bach.

The paintings in this room propose a metalanguage, about the dead and fictional language of painting, manipulating and combining dialects within this existing language from different centuries to recreate the spectres of lost or ‘potential’ artworks. A new ‘self-portrait’ of Rembrandt referencing several known self-portraits of the master at different ages. A ‘re-discovered’ Leonardo ‘Leda and the Swan’ referencing the ‘forbidden’ symbolism inherent in the existing lost work. Leonardo painted Leda and the Swan in 1508, the original was destroyed as the three conjoined panels split apart. Now lost, it was last seen in the court of Louis XIV. LENKIEWICZ’s re-enactment achieves an aura of authenticity by suturing together disparate elements from various Leonardo works - the rocks on the left from the Virgin of the Rocks, the swan from Melzi’s copy (see also Cezanne).

But the ‘new’ artist still has to create magic. And also has to be able to combine styles and techniques mostly abandoned in the late 20c. LENKIEWICZ is able to employ full mastery of the techniques utilised by the original artists, whether in theVelazquez Dwarf or the ‘new’ Mona Lisa, that the conceptual basis of his praxis fully embodies. Finally, in Fall of the Rebel Angels, Bruegel’s original apocalyptic vision is infiltrated by contemporary signifiers of destruction - warplanes, helicopters, drones, as the light of heaven is transformed into a luminous explosion. It is art history itself which LENKIEWICZ explodes.

www.riflemaker.org [email protected] 0207-439-0000 07794-629-188

MetaHistory

Wolfe von LENKIEWICZ (b. 1966) engages with the entire history of both classical and contemporary art by referring to key works in our visual consciousness and to the history which surrounds them. LENKIEWICZ is from Polish origins, descended from a dynasty of painters, his great-grandfather was the court painter to King Ludwig II of Bavaria.

Wolfe Lenkiewicz’s paintings propose a ‘metahistory’ of art, breaking with official history to fashion a new mythology - a history about the history of art.

In Postmodernism: Or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991) Fredric Jameson posited modernism as a critique of the ‘commodity’ and postmodernism as the consumption of commodification. Under postmodernism the act of consuming itself became a commodity. LENKIEWICZ does not position himself as a singular artist who, by his unique and extraordinary creations is going to change history. Instead, operating from the position of a meta-postmodernist observer, he investigates our mythological construction art history as a fiction - much as an improvising jazz pianist may outwardly appear to be in ‘free' improvisatory mode but subjectively may be referring to (and listening to) the exquisite harmonic sense of the music of JS Bach.

The paintings in this room propose a metalanguage, about the dead and fictional language of painting, manipulating and combining dialects within this existing language from different centuries to recreate the spectres of lost or ‘potential’ artworks. A new ‘self-portrait’ of Rembrandt referencing several known self-portraits of the master at different ages. A ‘re-discovered’ Leonardo ‘Leda and the Swan’ referencing the ‘forbidden’ symbolism inherent in the existing lost work. Leonardo painted Leda and the Swan in 1508, the original was destroyed as the three conjoined panels split apart. Now lost, it was last seen in the court of Louis XIV. LENKIEWICZ’s re-enactment achieves an aura of authenticity by suturing together disparate elements from various Leonardo works - the rocks on the left from the Virgin of the Rocks, the swan from Melzi’s copy (see also Cezanne).

But the ‘new’ artist still has to create magic. And also has to be able to combine styles and techniques mostly abandoned in the late 20c. LENKIEWICZ is able to employ full mastery of the techniques utilised by the original artists, whether in theVelazquez Dwarf or the ‘new’ Mona Lisa, that the conceptual basis of his praxis fully embodies. Finally, in Fall of the Rebel Angels, Bruegel’s original apocalyptic vision is infiltrated by contemporary signifiers of destruction - warplanes, helicopters, drones, as the light of heaven is transformed into a luminous explosion. It is art history itself which LENKIEWICZ explodes.

www.riflemaker.org [email protected] 0207-439-0000 07794-629-188

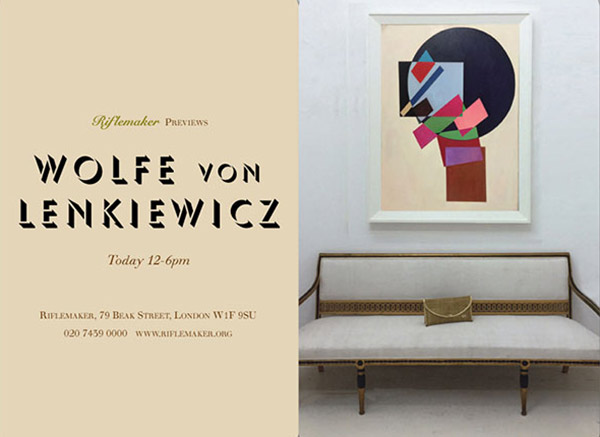

Previewing (at 79, Beak Street) new paintings by WOLFE von LENKIEWICZ

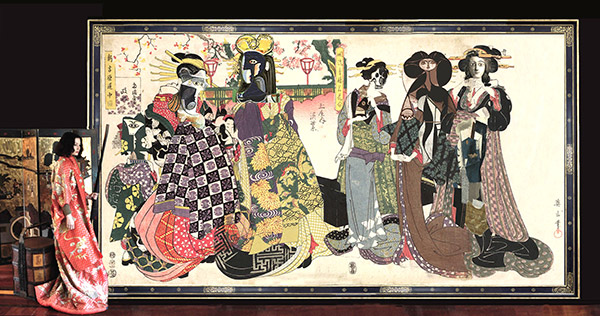

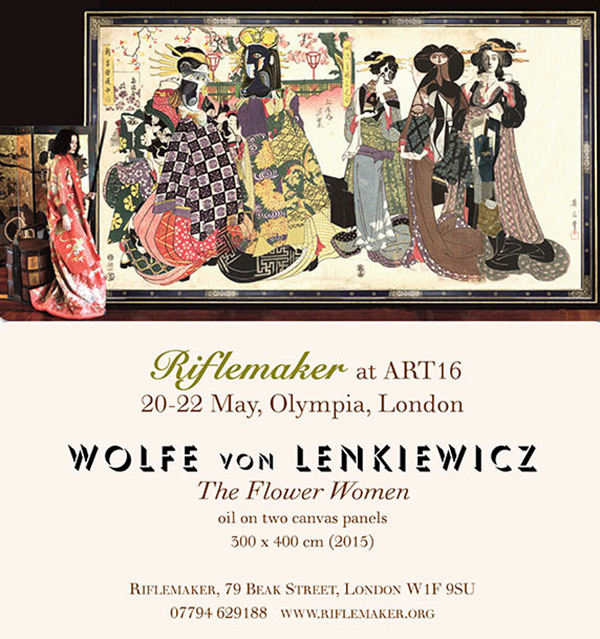

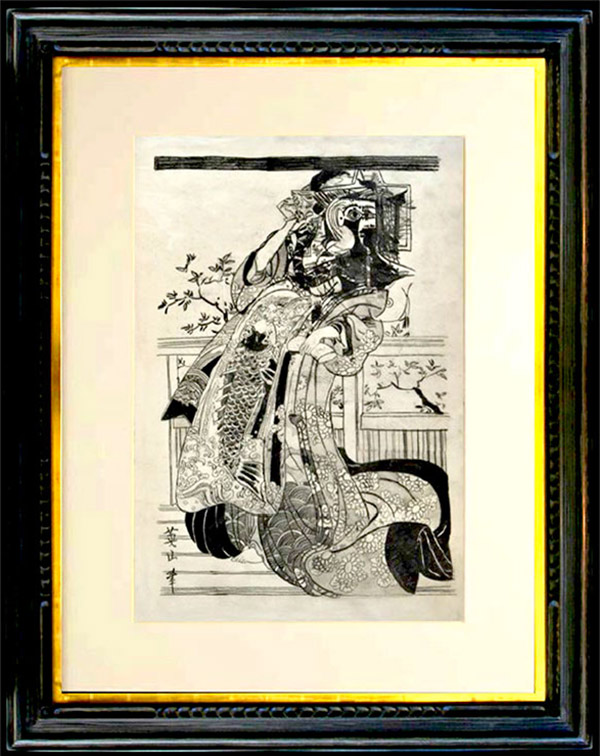

PICASSO IN CONTEMPORARY ART at Deichtorhallen, Hamburg, was an exhibition of ninety artists who have used Pablo Picasso in their work, including Wolfe von Lenkiewicz. From the same series and on a very grand scale The Flower Women (2016) embodies the notion of an artist in dialogue with another 'spirit'. Lenkiewicz (b. 1966) puts on Picasso's cloak and begins to trim and edit, adding the aesthetic of ukiyo-e (floating world) to a dramatic universe where East and West, ink and oil collide as the artist reconfigures, reimagines and reinvigorates one of the image-makers of our time.

Cubism meets Art Nouveau on a flat perspective where samurai, Gilot faces in silken robes and skeletal multi-profile figures become 'players' amid decorative flora and fauna - the 'inside out' stage-set inspired by the Japanese 19c master Kikukawa Eizan. The sheer ambition of the work, together with Lenkiewicz' deft handling of these disparate aesthetics conjure an extraordinary group portrait using the same principles Picasso himself employed while re-making Rembrandt and Velazquez.

In the Hamburg exhibition were works by Picasso himself and those influenced by him including Richard Prince and Lichtenstein, proving that creativity cannot exist without the past. Harold Bloom used the phrase 'The Anxiety of Influence' to describe the artist who wishes to cast himself as a genius of radical novelty by claiming no debt to past giants.

PICASSO IN CONTEMPORARY ART at Deichtorhallen, Hamburg, was an exhibition of ninety artists who have used Pablo Picasso in their work, including Wolfe von Lenkiewicz. From the same series and on a very grand scale The Flower Women (2016) embodies the notion of an artist in dialogue with another 'spirit'. Lenkiewicz (b. 1966) puts on Picasso's cloak and begins to trim and edit, adding the aesthetic of ukiyo-e (floating world) to a dramatic universe where East and West, ink and oil collide as the artist reconfigures, reimagines and reinvigorates one of the image-makers of our time.

Cubism meets Art Nouveau on a flat perspective where samurai, Gilot faces in silken robes and skeletal multi-profile figures become 'players' amid decorative flora and fauna - the 'inside out' stage-set inspired by the Japanese 19c master Kikukawa Eizan. The sheer ambition of the work, together with Lenkiewicz' deft handling of these disparate aesthetics conjure an extraordinary group portrait using the same principles Picasso himself employed while re-making Rembrandt and Velazquez.

In the Hamburg exhibition were works by Picasso himself and those influenced by him including Richard Prince and Lichtenstein, proving that creativity cannot exist without the past. Harold Bloom used the phrase 'The Anxiety of Influence' to describe the artist who wishes to cast himself as a genius of radical novelty by claiming no debt to past giants.

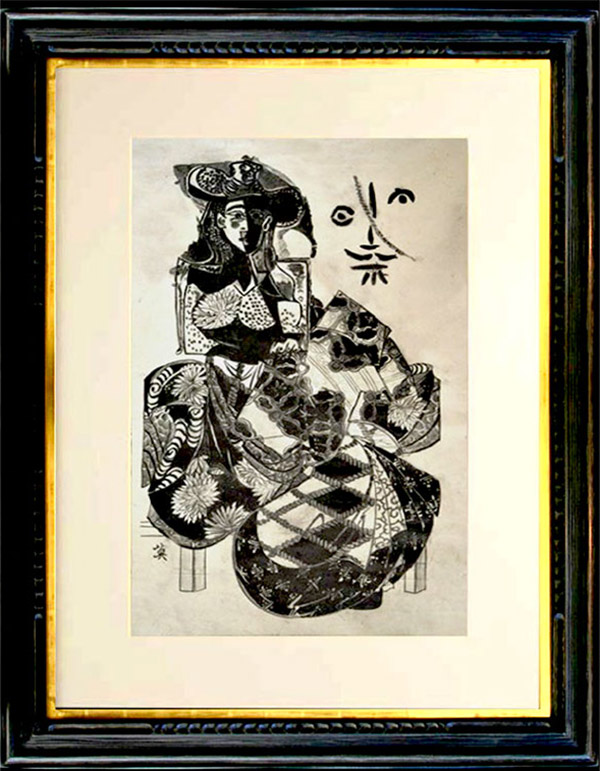

WOLFE von LENKIEWICZ

'Delirious Picasso 1'

'Delirious Picasso 1'

WOLFE von LENKIEWICZ

'Delirious Picasso 2'

'Delirious Picasso 2'

DELIRIOUS PICASSO' is an exhibition of works by the British artist Wolfe von Lenkiewicz. Known for his reconfigurations of well-known art historical imagery and contemporary visual culture, his latest series of paintings juxtaposes Picasso's oeuvre with the art of ukiyo-e to create a surprisingly harmonious marriage between East and West through a dramatic and riotous explosion of colour and style. The artist employs the flat perspective, translates the medium of ink into the medium of oil, adopts the fine vigorous line and the sumptuous use of colour and intricate pattern exemplified by Japanese wood block printing. Manifest is the work by Kikugawa Eizan, the late follower of Utamaro, known for the most part for his depiction of beautiful women (bijin-ga). The contradictory qualities inherent in Lenkiewicz's reassembled paintings defy convention whereby the refined elements of the floating world imagery seamlessly merge with the jaunty, syncopated rhythm and vitality of the figures that are synonymous with Picasso.

DELIRIOUS PICASSO comprises of 14 paintings that make up two distinct series of works entitled 'The Guards of the Void' and 'The Giants'. The 14 Picasso and Kikugawa reconfigured paintings each measure three by two meters. Familiar Picasso motifs appear, particularly the musketeer smoking long clay pipes, unified with courtesan and samurai figures, as well as fabrics, flora and fauna inspired by Japanese ukiyo-e. The sheer scale of the paintings together with Lenkiewicz' deft handling of these two seemingly disparate aesthetics, form an arresting series of portraits that demonstrate the reconcilable nature of Eastern and Western aesthetics and especially the different Cubist and ukiyo-e approaches. It is almost as if the Japanese has invented a more controlled version of Cubism a century before Picasso. Lenkiewicz's re-imagined paintings lead us reassuringly with the familiar and yet shocking us into a new evaluation of context and meaning.

What if Picasso had fully embraced the Japanese?

Although Picasso expressed an ambivalent attitude to the Japonisme movement and famously quipped to Gertrude Stein that he had no taste for the art of Japan, it was recently discovered that he personally owned more than sixty erotic prints, (otherwise known as shunga). It is apparent that echoes of the Far East, and Japan in particular, were central to his artistic genesis as were the tribal arts of Africa and Oceania. Harold Bloom used the term 'The Anxiety of Influence' to describe the artist who wishes to cast himself as a genius of radical novelty by claiming no debt to past giants.

One historian described Picasso's arrival on the Parisian art scene as that of 'a vertical invader', a sudden bolt of absolute novelty. The reputation for radicalism was an identity he gave himself and continued to perform for the rest of his artistic career. There are many overtures between Picasso and America, America and Japan, the East and the West that informs Picasso's work. Picasso's 'invasion' of America celebrated the 'New Spirit' with the spectacular Ballet Russes production Parade in Chicago (1917) and included performers wearing cardboard skyscrapers, playful new symbols denoting ambition, success and sex. The Beaux Arts Ball in New York (1931) subsequently featured architects wearing iconic skyscrapers costumes while giddily sipping champagne.

In 1860, the first delegation by the Japanese Embassy included 70 Samurai, who arrived in New York and became a celebrated parade and encounter between the two nations. Lenkiewicz' series The Giants is a metaphor for the samurai spectacle that dazzled New Yorkers. The two distant nations exerted considerable influence on each other in the 19th and 20th centuries both culturally and as trading nations. The title DELIRIOUS PICASSO refers to Delirious New York, a book by the architect Rem Koolhas (1978) that has today attained mythic status. A celebration and analysis of New York, it refers to Manhattan as "the 20th century's Rosetta Stone" and reinterprets the relationship between architecture and culture, the development of the skyscraper and Manhattan as a laboratory for invention and testing of a metropolitan lifestyle or 'the culture of congestion'.

DELIRIOUS PICASSO comprises of 14 paintings that make up two distinct series of works entitled 'The Guards of the Void' and 'The Giants'. The 14 Picasso and Kikugawa reconfigured paintings each measure three by two meters. Familiar Picasso motifs appear, particularly the musketeer smoking long clay pipes, unified with courtesan and samurai figures, as well as fabrics, flora and fauna inspired by Japanese ukiyo-e. The sheer scale of the paintings together with Lenkiewicz' deft handling of these two seemingly disparate aesthetics, form an arresting series of portraits that demonstrate the reconcilable nature of Eastern and Western aesthetics and especially the different Cubist and ukiyo-e approaches. It is almost as if the Japanese has invented a more controlled version of Cubism a century before Picasso. Lenkiewicz's re-imagined paintings lead us reassuringly with the familiar and yet shocking us into a new evaluation of context and meaning.

What if Picasso had fully embraced the Japanese?

Although Picasso expressed an ambivalent attitude to the Japonisme movement and famously quipped to Gertrude Stein that he had no taste for the art of Japan, it was recently discovered that he personally owned more than sixty erotic prints, (otherwise known as shunga). It is apparent that echoes of the Far East, and Japan in particular, were central to his artistic genesis as were the tribal arts of Africa and Oceania. Harold Bloom used the term 'The Anxiety of Influence' to describe the artist who wishes to cast himself as a genius of radical novelty by claiming no debt to past giants.

One historian described Picasso's arrival on the Parisian art scene as that of 'a vertical invader', a sudden bolt of absolute novelty. The reputation for radicalism was an identity he gave himself and continued to perform for the rest of his artistic career. There are many overtures between Picasso and America, America and Japan, the East and the West that informs Picasso's work. Picasso's 'invasion' of America celebrated the 'New Spirit' with the spectacular Ballet Russes production Parade in Chicago (1917) and included performers wearing cardboard skyscrapers, playful new symbols denoting ambition, success and sex. The Beaux Arts Ball in New York (1931) subsequently featured architects wearing iconic skyscrapers costumes while giddily sipping champagne.

In 1860, the first delegation by the Japanese Embassy included 70 Samurai, who arrived in New York and became a celebrated parade and encounter between the two nations. Lenkiewicz' series The Giants is a metaphor for the samurai spectacle that dazzled New Yorkers. The two distant nations exerted considerable influence on each other in the 19th and 20th centuries both culturally and as trading nations. The title DELIRIOUS PICASSO refers to Delirious New York, a book by the architect Rem Koolhas (1978) that has today attained mythic status. A celebration and analysis of New York, it refers to Manhattan as "the 20th century's Rosetta Stone" and reinterprets the relationship between architecture and culture, the development of the skyscraper and Manhattan as a laboratory for invention and testing of a metropolitan lifestyle or 'the culture of congestion'.